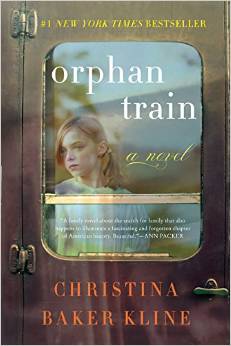

I found the novel Orphan Train sitting on the Staff Pick shelf in my local branch of the Toronto Public Library. I had never heard of this title, nor read other works by the author, Christina Baker Kline. Yet, something lifted my arm and forced my hand to grip the book. Yes, yes, call me sappy. I’m a sucker for orphan stories. But isn’t everyone? Judging by the vast number of popular novels featuring orphans, including The Secret Garden, Anne of Green Gables, Tom Sawyer, Oliver Twist and most recently, the Harry Potter series, I sense that many writers and readers are as attracted to fictional orphans as I am. But what do we talk about when we talk about orphans in literature? Orphan Train, while not in the upper echelons of orphan lit, may provide some clues.

I found the novel Orphan Train sitting on the Staff Pick shelf in my local branch of the Toronto Public Library. I had never heard of this title, nor read other works by the author, Christina Baker Kline. Yet, something lifted my arm and forced my hand to grip the book. Yes, yes, call me sappy. I’m a sucker for orphan stories. But isn’t everyone? Judging by the vast number of popular novels featuring orphans, including The Secret Garden, Anne of Green Gables, Tom Sawyer, Oliver Twist and most recently, the Harry Potter series, I sense that many writers and readers are as attracted to fictional orphans as I am. But what do we talk about when we talk about orphans in literature? Orphan Train, while not in the upper echelons of orphan lit, may provide some clues.

Orphan Train weaves a multi-layered story around a neglected, but significant moment in American history. Between 1854 and 1929, more than two hundred thousand orphaned, abandoned, and homeless children — typically first generation Irish, Italian and Polish immigrants — were transported by train from coastal cities of the eastern United States to the Midwest. As is often the case, the founder of the program believed he was saving helpless children from the depravity and poverty associated with urban dwelling at the time. His plan for the so-called adoption of these children by Midwestern Christian families turned out to be, in most instances, nothing more than indentured servitude. Kline’s novel features a ninety-one year old survivor of the program. Vivian Daly’s experience as an orphan-train rider unfolds while revealing her hidden past to Molly Ayer, a Penobscot Indian teenager living in foster care with a different family. Molly is fulfilling her community service hours by helping Vivian clean her attic. The narrative alternates between the stories of these two very different women, both orphans, who build an unexpected friendship.

It is easy to dismiss the contrived plot of Orphan Train and the forced connection between Vivian and Molly. The gaps in their age and culture would seem to make any relationship between the two women highly unlikely. Yet, their shared orphan identity creates a strong thematic bond that overrides the novel’s obvious contrivances. The more Molly assists Vivian to sort through her possessions and the memories associated with these secret objects, the more she discovers the parallels in their lives. As a Penobscot Indian, Molly is an outsider being raised by strangers in foster care, just as Vivian once was. Both women are characters out of place, compelled to make a home for themselves in alien families.

In literature, however, these two women are not aliens at all. Indeed, they are right at home, cut from the same cloth as other beloved orphans, such as Cinderella, Heidi, Jane Eyre and Anne Shirley. In Orphan Train, the author takes the traditional literary trope of the orphan protagonist and tweaks it by making Molly unappealingly Goth and not particularly virtuous. Little Goody Two-Shoes — another famous orphan in fiction — Molly is not. Her hair is dyed jet-black, accented with purple or white streaks. And she steals. Okay the stolen booty just happens to be a tattered copy of Jane Eyre from the town library. How bad (and ironic) is that? Still, Molly and Vivian are essentially novelistic characters, set loose from the established conventions of family life, always in search of some sort of closure. As Kazuo Ishiguro notes in his novel, When We Were Orphans, “For those like us, our fate is to face the world like orphans, chasing through long years the shadows of vanished parents.”

What interests me most in Orphan Train is not the resilience which Vivian and Molly demonstrate. Most novels about orphans are narratives of second chances. But more significantly, there’s is a real social history behind these fictional orphans. Time and place do matter. And for orphans, context is everything. They are uprooted individuals who must interact with an unknown, yet precisely defined set of circumstances to survive. When we talk about orphans in literature, we are talking about their interaction with new spaces that will shape them, perhaps even define them, like laboratories of tomorrow.